Penetration Testing vs. Red Teaming: What’s Right for Your Organization?

This blogpost explains the differences, benefits, and when each is the right choice to strengthen your organization’s security and resilience.

Introduction

Enterprises and DORA-regulated firms in Europe face increasing pressure to strengthen cyber resilience. A common question is whether to engage in penetration testing or red teaming – or both – to test their defenses.

This blog-post clarifies the differences, benefits, and use cases of each approach, drawing on global standards and European regulatory context. We compare objectives, methodologies, duration, costs, and ROI, and outline how organizations can choose the right approach based on their maturity.

TL:DR

Before doing a red team, an organization should have alerting/logging (either in-house or via an MSSP) and some idea of which TTPs they can detect, plus patching programs in place. For ROI comparison and Case Studies, search for 'ROI' in this blog-post.

Defining Penetration Testing vs. Red Teaming

Penetration Testing (Pentesting): According to NIST SP 800-115, “penetration testing is security testing in which assessors mimic real-world attacks to identify methods for circumventing the security features of an application, system, or network.” [nvlpubs.nist.gov] In practice, a pentest is a focused, authorized hacking attempt on specific targets to uncover as many technical vulnerabilities as possible within a defined scope and timeframe. Pentesters typically use a mix of automated scanning tools and manual exploit techniques to find weaknesses, then document the findings and remediation steps. The Penetration Testing Execution Standard (PTES) outlines a clear process for these engagements in seven phases – from pre-engagement planning through reconnaissance, vulnerability analysis, exploitation, and reporting [blog.rsisecurity.com]. Other well-known methodologies like the OWASP Web Security Testing Guide (for web applications) provide detailed checklists for testers to ensure thorough coverage of common flaws. The primary goal of a pentest is to identify and verify vulnerabilities before attackers do, providing a prioritized list of security gaps to fix [cycognito.com]. Pentests are often time-boxed (e.g. one to two weeks for a given system) and confined to certain systems or applications agreed upon in advance. They tend to be overt (i.e. the organization’s IT team may know a test is occurring) and are sometimes repeated regularly (e.g. quarterly or annually) for compliance or best-practice. As a NIST guide notes, because pentests use real exploits against production systems, they carry some risk and thus should be carefully scoped and planned [nvlpubs.nist.gov, nvlpubs.nist.gov]. Many organizations use pentesting to meet standards or regulations – for example, to satisfy PCI DSS requirements or as part of ISO 27001 certification – and frameworks like OWASP WSTG, PTES, and NIST 800-115 are commonly referenced to ensure a rigorous approach.

Red Teaming: Red teaming is a form of adversarial simulation that is broader in scope and more goal-oriented than standard pentesting. In a red team exercise, a team of ethical hackers (the “red team”) conducts a simulated real-world attack on an organization – often spanning digital, physical, and social engineering vectors – to test not just technical vulnerabilities but the organization’s detection and response capabilities. A red team engagement is essentially a full-fledged cyber-attack rehearsal. As one definition puts it, “red teaming is a full-scope, goals-focused adversarial simulation exercise that incorporates physical, electronic and social forms of attacks.” [kroll.com] The red team uses the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) of real threat actors, often operating covertly for extended periods to see how far they can get without being caught [cycognito.com]. Unlike pentesting, which might stop at confirming a vulnerability, red teaming usually pursues specific objectives (e.g. gain domain admin access, obtain confidential data, or penetrate critical operations) while evading detection. This approach is grounded in military and intelligence practices – frameworks like the MITRE ATT&CK matrix and the Lockheed Martin Cyber Kill Chain are frequently used to plan and communicate red team operations. For example, red team operators map their attack steps to the MITRE ATT&CK tactics to ensure they emulate a broad range of adversary behaviors [cycognito.com]. They move through kill-chain phases such as reconnaissance, initial compromise, lateral movement, and data exfiltration, just as an advanced persistent threat (APT) would [cycognito.com]. Red teaming often includes things a pentest might not, such as phishing employees, tailgating into offices, planting rogue devices, or testing the incident response process. The overarching aim is to test the organization’s overall security posture – including people and processes – and its ability to detect, respond to, and recover from a sophisticated attack [cycognito.com, cycognito.com]. Because of this broader scope, red team exercises are typically only undertaken by organizations with more mature security programs (e.g. those that have already addressed basic vulnerabilities and have monitoring/response mechanisms in place). Red teaming exercises are usually longer engagements (often running several weeks or months) and are conducted with only a small group of senior stakeholders aware it’s a drill – everyone else (the “blue team” defenders) is expected to react as if it were a real intrusion [kroll.com, kroll.com].

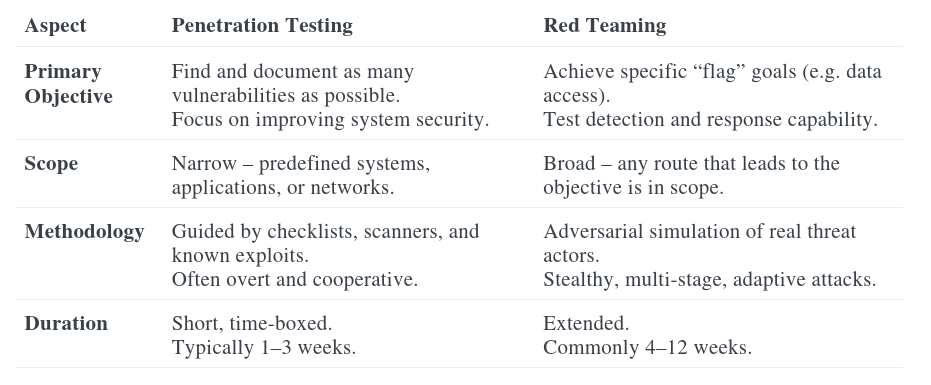

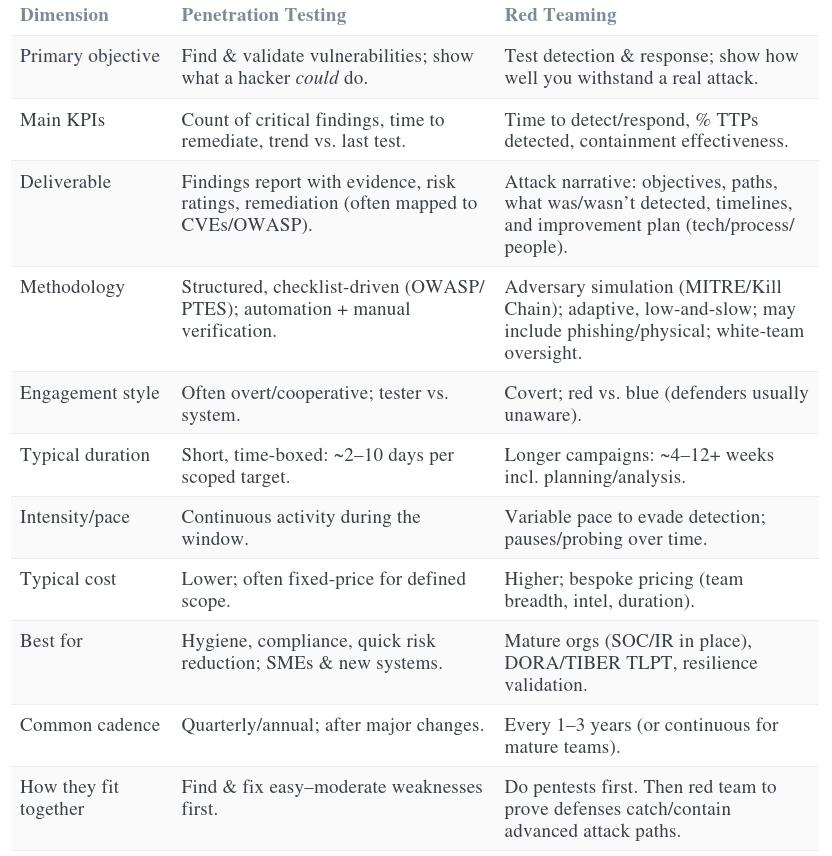

Key Differences: In summary, penetration testing focuses on breadth of vulnerabilities in a given scope, whereas red teaming focuses on depth of compromise and response across an organization. A succinct comparison from CyCognito’s security blog is: “Penetration testing focuses on identifying technical vulnerabilities within a system, while red teaming simulates real-world attacks with the goal of testing the overall security posture and incident response capabilities.” Red teaming has a broader scope, potentially including social engineering and physical breaches, and is typically used by organizations with mature defenses [cycognito.com]. The table below contrasts the two approaches on key aspects:

Both approaches ultimately aim to improve security, but they do so in different ways. Many organizations start with penetration testing to fix known weaknesses and satisfy compliance, then “graduate” to red teaming when they want to stress-test their detection and response or meet higher regulatory requirements.

Global Standards and Frameworks Referenced

When implementing pentesting or red teaming, it’s wise to align with established standards to ensure rigor and credibility:

- NIST SP 800-115 (Technical Guide to Information Security Testing): The NIST framework (from the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology) offers guidance on planning and conducting security assessments, including penetration testing [nvlpubs.nist.gov, nvlpubs.nist.gov]. It emphasizes careful planning, rules of engagement, and post-test analysis. NIST defines various test techniques (vulnerability scanning, pentesting, social engineering, etc.) and highlights the benefits and limitations of each. For example, NIST cautions that pentesting is labor-intensive and “poses a high risk to the organization’s networks and systems because it uses real exploits and attacks against production systems” – hence it should be done with management approval and clear rules [nvlpubs.nist.gov, nvlpubs.nist.gov]. NIST SP 800-115’s influence can be seen in many organizations’ penetration testing policies worldwide.

- OWASP Testing Guides: The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) provides the Web Security Testing Guide (WSTG) as a community-driven standard for web application penetration tests. It covers everything from information gathering to business logic testing, ensuring that testers follow a comprehensive checklist of potential web app vulnerabilities. OWASP’s guides and OWASP Top 10 risks are often used to scope and report pentest findings (e.g. checking for SQL injection, XSS, CSRF, etc.). Additionally, OWASP has frameworks for mobile app testing and even an OWASP Penetration Testing Methodologies overview that references other standards (like PTES and NIST) [owasp.org].

- Penetration Testing Execution Standard (PTES): PTES is a well-known standard that breaks a penetration test process into seven logical phases: Pre-Engagement, Intelligence Gathering, Threat Modeling, Vulnerability Analysis, Exploitation, Post-Exploitation, and Reporting [blog.rsisecurity.com]. It provides both a high-level roadmap and detailed technical guidelines for each phase. Many consulting firms base their methodology on PTES, ensuring that they not only attempt exploits but also do proper recon and post-exploit cleanup. PTES also encourages discussing threat modeling with clients – to understand which assets are most critical – which increases the relevancy of pentest results.

- MITRE ATT&CK: This is a globally accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques, which has become a cornerstone for red team operations. Red teams use MITRE ATT&CK to map out which tactics (phases like initial access, privilege escalation, lateral movement, etc.) and specific techniques they will emulate. By doing so, they can communicate in a standard language with the defense (blue team) about what was or was not detected. It also helps ensure coverage of a broad range of real-world techniques. As Palo Alto Networks notes, “red teaming becomes more impactful when emulated activity aligns with MITRE ATT&CK”, allowing the results to pinpoint defensive gaps in specific technique areas [exabeam.com]. In practice, a red team might say “we executed technique T1566 (phishing) to get initial access” – and later the organization can check if their controls detected that. MITRE ATT&CK doesn’t tell you how to red team, but it is an invaluable reference to ensure completeness and to structure findings.

- Lockheed Martin Cyber Kill Chain: The “kill chain” model (Reconnaissance → Weaponization → Delivery → Exploitation → Installation → Command & Control → Actions on Objectives) is often used in tandem with MITRE ATT&CK. It provides a high-level lifecycle view of an attack. Red teams use the kill chain to plan multi-stage operations and to brief executives in understandable terms (e.g. explaining which stage an attack was detected at, or how far along the kill chain they got). As a SANS Institute piece noted, the kill chain is useful for explaining high-level goals to non-practitioners, while ATT&CK provides the technical detail [sans.org]. Many red team reports are structured around kill chain stages to show how an attacker could progress if not stopped.

- Adversary Emulation Plans: In advanced red teaming, teams may use published adversary profiles or emulation plans (often from MITRE or intelligence agencies) to mimic known threat groups. For example, MITRE’s APT29 emulation plan provides a step-by-step playbook of how a specific nation-state group operates, which red teams can emulate to test a target’s readiness for that adversary. This brings a threat intelligence-led angle to red teaming.

- Industry-Specific Frameworks (CBEST, TIBER-EU, etc.): In certain sectors, regulators have developed their own red teaming frameworks. In financial services, the Bank of England’s CBEST (for UK) and the European Central Bank’s TIBER-EU are prominent. These frameworks standardize how to conduct threat intelligence-based red teaming for critical financial infrastructure. TIBER-EU (Threat Intelligence-Based Ethical Red Teaming) in particular is now a common reference in Europe – it provides comprehensive guidance on running a controlled red team test, including the roles of external Threat Intel providers, red team providers, and how regulators should oversee the test. TIBER-EU tests “mimic the tactics, techniques and procedures of real-life attackers, based on bespoke threat intelligence” and target an entity’s critical functions [ecb.europa.eu]. The outcome isn’t a simple pass/fail, but a detailed improvement plan. We’ll discuss TIBER-EU more in the DORA context below, but it’s worth noting here that many top red teaming providers in Europe align their services to TIBER-EU’s requirements. (For example, firms advertise being “TIBER-EU ready” or having experience with TIBER engagements.)

In summary, penetration testing engagements often cite standards like NIST, PTES, and OWASP to demonstrate a methodical approach and compliance, while red team engagements draw on attack frameworks (MITRE ATT&CK, Kill Chain) and often adhere to sector-specific schemes (like TIBER-EU for finance) to ensure realism and credibility.

European Regulatory Context: DORA and TIBER-EU

Europe’s cybersecurity regulations have been evolving, with significant implications for how often and how rigorously organizations must test their defenses. Two key elements for the financial sector are DORA and TIBER-EU:

- DORA (Digital Operational Resilience Act): DORA is an EU regulation focused on financial entities’ ability to withstand digital disruptions and cyberattacks. It came into force on 17 January 2025, requiring banks and other financial services firms in the EU to implement robust operational resilience measures [taylorwessing.com]. A headline requirement in DORA is for “advanced testing” of ICT security by means of threat-led penetration testing (TLPT). Specifically, in-scope financial entities designated by regulators must carry out a threat-led red team test at least every 3 years [digital-operational-resilience-act.com]. These tests must cover critical systems and be conducted on production infrastructure, under oversight of the regulator. DORA effectively mandates regular red team exercises for major financial institutions, making the EU one of the first jurisdictions to require this by law. The regulation tasks the European Supervisory Authorities (EBA, ESMA, EIOPA) with developing Regulatory Technical Standards for how TLPT should be conducted (covering scope, methodology, phases of testing, etc.) [digital-operational-resilience-act.com, digital-operational-resilience-act.com]. The principle is proportionate regulation – smaller institutions with lower risk profiles may not be tested as stringently [taylorwessing.com], but large banks and insurers will likely face full-scope red team exercises overseen by their regulators. The tests must be performed by accredited external testers (or internally, but independent from the targets) and observed by the regulator. After the test, firms need to report results and remediation plans to the regulator, who can then issue an attestation of the test’s completion [digital-operational-resilience-act.com]. In short, DORA explicitly elevates red teaming from a best-practice to a legal requirement for Europe’s financial sector. This is driving demand for sophisticated red teaming services among banks, fintechs, and other regulated firms, as the deadline for compliance approaches. It’s also fostering alignment across EU countries, so that a test done in one country is recognized by others (to avoid each country imposing separate tests on multi-national banks).

- TIBER-EU: TIBER-EU is the European Central Bank’s framework for performing threat-intelligence led red team tests. Introduced in 2018, it was voluntary but widely adopted by many EU member states’ central banks. In 2024, TIBER-EU was updated to fully align with DORA’s TLPT requirements [ecb.europa.eu]. In fact, the ECB explicitly states that TIBER-EU can help financial entities meet the threat-led testing obligations under DORA [ecb.europa.eu]. TIBER-EU provides a common playbook so that a bank in, say, the Netherlands and one in Austria undergo similarly rigorous tests with mutual recognition of results. Under TIBER-EU, a test involves a collaboration between the entity, a Threat Intelligence (TI) provider, and a Red Team provider, with the national central bank as the overseer. The TI provider first develops a realistic threat scenario based on current threat intel (e.g. identifying likely threat actors and their TTPs against that bank). Then the Red Team provider uses that scenario to conduct an attack exercise, while the entity’s security team (unaware of details) hopefully detects and responds. A Control Team within the entity (trusted personnel) coordinates logistics and ensures safety (so the test doesn’t unintentionally disrupt critical operations). The test ends with a Purple Team phase – a collaborative debrief where red and blue share results and improvement steps [ecb.europa.eu]. TIBER-EU is now adopted in many countries: as of 2024, Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden and the ECB itself all have TIBER programs [ecb.europa.eu, ecb.europa.eu]. Notably, the Czech National Bank joined TIBER-EU in 2024 in anticipation of DORA, signaling to Czech banks that such testing will be required [taylorwessing.com, taylorwessing.com]. Under the Czech TIBER implementation, for example, all relevant banks must undergo threat-led penetration testing at least once every three years, with the CNB selecting institutions annually for testing [taylorwessing.com]. Other EU countries are similarly integrating DORA’s requirements via their TIBER or equivalent schemes.

For SMEs outside the financial sector, DORA may not apply directly – however, the NIS2 Directive (which covers a broader range of industries) and national regulations are also raising the bar for cybersecurity testing in Europe. NIS2 stops short of mandating red teams, but it does require risk-based security assessments and could indirectly spur more pentesting for critical medium-sized companies in sectors like energy, transport, health, etc. Meanwhile, DORA’s influence might extend beyond finance; vendors and service providers to financial institutions may be asked to participate in tests or shore up their security.

Impact on Need for Pentesting or Red Teaming: In Europe, the regulatory push is clear: if you’re a financial entity (bank, payment provider, insurance, etc.), you will need robust penetration testing and likely periodic red team exercises to comply with DORA. Even if you’re an SME, if you fall under a regulator (e.g. a fintech under a central bank, or a cloud provider supporting banks), you may be indirectly pulled into this requirement. DORA is essentially making red teaming a standard practice for resilience – something that historically only the largest banks did, but now mid-sized firms in finance must plan for it too. TIBER-EU provides the playbook, which means many organizations will prefer security vendors who are familiar with TIBER and can deliver tests in that format. Outside of finance, regulations like GDPR (for data protection) and sectoral laws encourage regular security testing, albeit not as prescriptive as DORA.

For SMEs not under strict mandates, the European context still matters: the rise in attacks and general due diligence expectations (from partners or customers) mean that showing you conduct independent security testing can be a competitive advantage or even a requirement in contracts. In critical sectors, regulators might not force a full red team on a small supplier, but they will expect basic pentesting and perhaps scenario-based testing as part of incident response preparedness.

Summary: Europe is moving from a world where penetration testing was often an annual “checkbox” for compliance, to a world where sophisticated, threat-informed testing (like red teaming) is becoming the norm for critical organizations. DORA’s every-three-years red team mandate and frameworks like TIBER-EU are driving this change [digital-operational-resilience-act.com, ecb.europa.eu]. Organizations should assess their readiness: Are your basic vulnerabilities under control (so a pentest won’t just find low-hanging fruit)? Do you have logging and incident response in place to make a red team exercise worthwhile? We’ll discuss these maturity considerations next.

Comparing Objectives, Deliverables, Methodologies, Duration, and Costs

Let’s dive deeper into how penetration testing and red teaming differ along practical dimensions, and what you can expect when engaging in each:

In practice, many organizations use both approaches in a complementary fashion. For example, an SME might do quarterly pentests on various assets to keep vulnerabilities in check, and then annually or biennially engage a red team to simulate a more dangerous scenario (perhaps assuming some baseline vulnerabilities exist, to test incident response). Pentesting results feed into patching and hardening; red team results feed into improving monitoring, policies, and procedures.

The choice is not necessarily either/or, but “when and in what order.” A common recommendation: ensure you have a solid vulnerability management and patching process (validated by regular pentests) before doing a red team. Otherwise, a red team will simply exploit an unpatched known flaw and declare “game over” on day one – which is a waste of a red team engagement if basic cyber hygiene is missing. Red teaming is most valuable when an organization has already fixed easy issues and wants to simulate a skilled, determined adversary to see what more they could do.

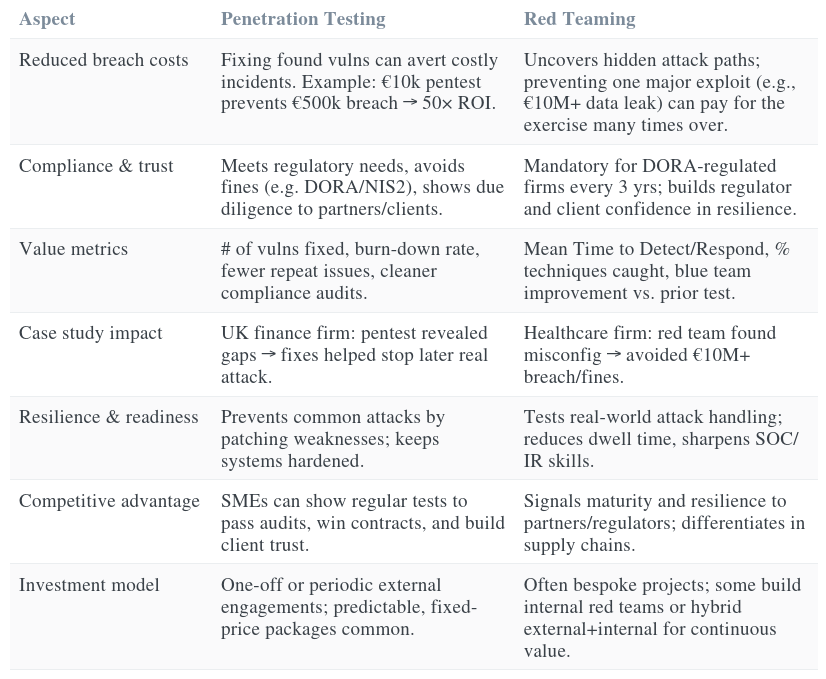

ROI and Case Studies: Value and Impact for SMEs and Regulated Firms

Investing in security testing should ultimately reduce risk – but how can organizations quantify the return on investment (ROI) of penetration testing or red teaming? While it’s challenging to put concrete numbers on prevented breaches, there are data points and case studies that illustrate the value:

In summary, the business case for penetration testing lies in preventing common cyber incidents and meeting compliance obligations – relatively straightforward to justify as an insurance measure. The business case for red teaming lies in preparing for sophisticated attacks and ensuring that if (or when) a major attack occurs, the organization can handle it with minimal damage. As the adage goes, “If you think hiring a professional is expensive, try hiring an amateur.” Similarly, investing in a controlled attack (red team) is far cheaper than dealing with a real uncontrolled attack.

From DORA-regulated financial firms to tech SMEs, case studies consistently show that money spent on finding and fixing security gaps (offensive testing) is dwarfed by the money saved from breaches averted or mitigated. For example, Trustwave reported a case where a UK financial firm’s management was convinced to invest in pentesting after initial tests showed unseen vulnerabilities – later, an attempted real attack was foiled partly because the pentest had led them to bolster that area [trustwave.com]. This illustrates the point: testing shines a light on unknown problems, which you can then fix – the ROI is avoiding being blindsided by those problems in the wild.

Organizational Maturity Requirements for Each Approach

One critical consideration when choosing between pentesting and red teaming is the organization’s cybersecurity maturity. In simple terms, Are you ready for a red team exercise, or should you focus on pentesting first? Here are some maturity markers and prerequisites:

For Penetration Testing: Virtually any organization with an IT system can benefit from a penetration test. There is not a high maturity bar to start pentesting – it’s often the entry point of security assurance. Even a startup should consider a pentest of their web app before going live. However, to get value, you should at least have some basic things in place: an inventory of your critical systems (so you know what to test), a process to patch or fix issues found (otherwise testing is just an academic exercise), and backups/contingency plans in case something goes wrong (pentesters strive not to disrupt, but there’s always a non-zero risk of a system crash). Many smaller companies start with a vulnerability scan or assessment as a lighter-weight approach, then graduate to a full penetration test when they have the resources. Notably, pentesting can be outsourced entirely – you don’t need in-house security staff to undergo a pentest (the provider will do the heavy lifting and explain results to IT). So the maturity needed is more about IT management and openness to fix problems.

For Red Teaming: Most experts and providers agree that red teaming should come after an organization has achieved a certain baseline of security maturity. Kroll advises that “an organization should meet a certain minimum level of maturity in order to get the most value out of a red team exercise”, specifically recommending that the organization have alerting, logging, and monitoring in place, and a handle on what tactics they can detect [kroll.com]. In other words, if you have no intrusion detection capability – no SOC or SIEM monitoring logs – a red team will waltz through and you’ll only know what they did when the final report drops. That’s not ideal; you would have learned almost as much from a cheaper pentest. Red teaming is most effective when there’s a competent blue team to challenge. Some maturity indicators that signal readiness for red teaming include:

- A functioning Security Operations Center (SOC) or at least an incident response plan and monitoring of critical systems. (If something odd happens, will someone notice and react?)

- Vulnerability management in place – i.e. you regularly scan and patch high-risk issues. This ensures the red team isn’t just exploiting a 3-year-old unpatched bug that you should have caught already.

- Basic security controls deployed: firewalls, endpoint protection, EDR (Endpoint Detection & Response) solutions, etc., that the red team can test and that could generate alerts.

- Trained personnel: Your IT/security staff have received some training in incident detection/response (maybe even done drills or tabletop exercises). A red team can then serve as a realistic test of that training.

- Management buy-in: Red teams can produce uncomfortable results (“we completely compromised everything and nobody noticed”). Leadership needs to be mature enough to handle that constructively, investing in improvements rather than assigning blame. If the corporate culture isn’t ready for potentially stark truths, it may undermine the red team’s impact. Ideally, management explicitly wants to “test our incident response and improve it.”

Kroll specifically mentions that an organization should have alerting/logging (either in-house or via an MSSP) and some idea of which TTPs they can detect, plus patching programs in place, before doing a red team [kroll.com]. They also mention budget as a factor – if you can’t afford the length of a full red team, a scaled-down targeted exercise might be better [kroll.com]. This ties to maturity: more mature orgs tend to have bigger security budgets.

How SPARK42 Can Help

At SPARK42, we combine hands-on technical expertise with deep knowledge of European regulations like DORA and TIBER-EU. For enterprise, we deliver cost-effective penetration tests aligned to standards such as OWASP, PTES, and NIST – giving you clear, actionable insights to reduce risk and demonstrate compliance. For regulated financial institutions and mature organizations, our red team exercises simulate advanced, real-world threats to test your detection and response capabilities, always tailored to your critical business functions. Whether you’re aiming to close technical gaps or prove operational resilience, SPARK42 helps you strengthen security, meet regulatory expectations, and build trust with customers and regulators.